Self-Hosting with Docker Compose

My repeatable Docker Compose + systemd pattern for homelab services, including Traefik, Cloudflare DNS-01, and backup-friendly volume layouts.

Overview

I self-host a lot of little services - everything from Jellyfin, Pi-Hole, to Cyberchef to the occasional throwaway prototype. After years of tinkering, I've started to basically set them up the same way every single time. The pattern is:

- Purpose-built Ubuntu 24.04 VM with Docker installed (a VM in my ProxMox cluster)

- Docker Compose for whatever the service I want to run

- An unprivileged

service-runneruser with specificsudoprivileges - An

/opt/{service-name}folder to store everything (Docker Compose,.env, and all related data) - A

systemdservice daemon to manage the Docker Compose - Using Traefik in front of the service so that I safely expose only certain ports and I get free LetsEncrypt SSL certificates for services inside my private network, via Cloudflare DNS challenge

This post walks through that repeatable pattern, why it works for my homelab, and the trade-offs you should understand before copying it.

TL;DR

In this post, I'll cover why Docker Compose hits the sweet spot between one-off

docker runcommands and full-blown Kubernetes, how I bootstrap new services with a systemd-managed skeleton (service-generator.sh), how Traefik plus Cloudflare DNS-01 gives me HTTPS on a private network, and why I keep every file for a service inside/opt/{service-name}to simplify backups.

Problem Statement

Self-hosting means running the apps you depend on - Pi-hole, CyberChef, Draw.io, Plex, Linkding, whatever - on hardware you control in your homelab instead of paying for SaaS. It’s empowering and a lot of fun, but it gets complicated fast if each service has a bespoke setup. It's stops being fun when you've created a big, unmanageable mess. I needed one predictable, reproducible "system" so that six months later I could remember how it all works.

Self-hosting also gives you privacy, the ability to hack on features, and fewer monthly subscriptions, but it does move the "ops burden" into your basement rack.

Docker by itself wasn’t quite enough. Typing long docker run commands from memory, dealing with random networks, and wiring reverse proxies manually is brittle. On the opposite end, Kubernetes (or even Docker Swarm) adds a mountain of operational complexity I don’t want in a single-node lab. Docker Compose proved to be the Goldilocks option: declarative, predictable, and friendly to Traefik. In other words, docker alone is too little, and k8s is too much.

What’s a Docker Volume Mapping? It’s simply a link between a folder on your host (

/opt/bookstack/db/) and a path inside the container (/var/lib/mysql). Containers see a stable filesystem path, and you control exactly where the data lives. Within Docker and Docker Compose you can create that mapping to a "volume" that Docker manages for you, or you can bind-mount a specific host folder like I do. The big difference is:

- Docker Managed - your files are somewhere else on the file system, and you have to go hunt them down for your backup scheme. Example:

db-data:/var/lib/mysql- where in real life, thatdb-datais likely in/var/lib/docker/volumes/db-data/_data/- Bind Mount - this is where you link a specific host folder into the container, giving you direct access to the files. Example:

/opt/bookstack/db/:/var/lib/mysql

Why I Standardize on Docker Compose

Especially if you come from an enterprise background, Kubernetes is the answer for everything. You may not even know that Docker Compose exists! It does however solve a lot of problems where: Docker alone is too simple and incapable, and Kubernetes is way, way, way, way, way, way too overkill. For example:

- Multi-container topologies: Compose makes it super simple to ship: Postgres, an app container, Redis cache, and Traefik labels as one unit without shell scripts. They all come up and go down as one big "service", and you can set up dependencies, health checks, etc.

- Readable networking: I can name networks, rely on service discovery, and keep random ports closed off from the rest of my LAN. I can have my app frontend talk to the database over a private Docker network where that network traffic is not visible outside of that host, and no unnecessary ports are exposed.

- Declarative configuration: All env vars, labels, and volume mappings can live in version-controlled YAML, so I can rebuild from scratch with confidence.

- Systemd integration: Compose is still just Docker, so systemd can

ExecStart=/usr/bin/docker compose up -dwhich makes this "service" look, act, and feel like any other native Linux service. - There are downsides!: There’s no built-in high availability. If I reboot the node, clients wait until that host comes back. For a single server homelab that’s fine, but for a production environment, you’d want to consider clustering or other HA solutions.

What’s Cloudflare? It’s a DNS and security platform. I use it because their API makes DNS-01 certificate challenges painless, and I already host my domains there. Meaning, we can configure our reverse proxy, Traefik to ask Cloudflare to add a temporary

TXTrecord to our DNS, then ask LetsEncrypt to verify it, and then LetsEncrypt will issue us an SSL certificate for our website (for free).

The Repeatable Service Pattern

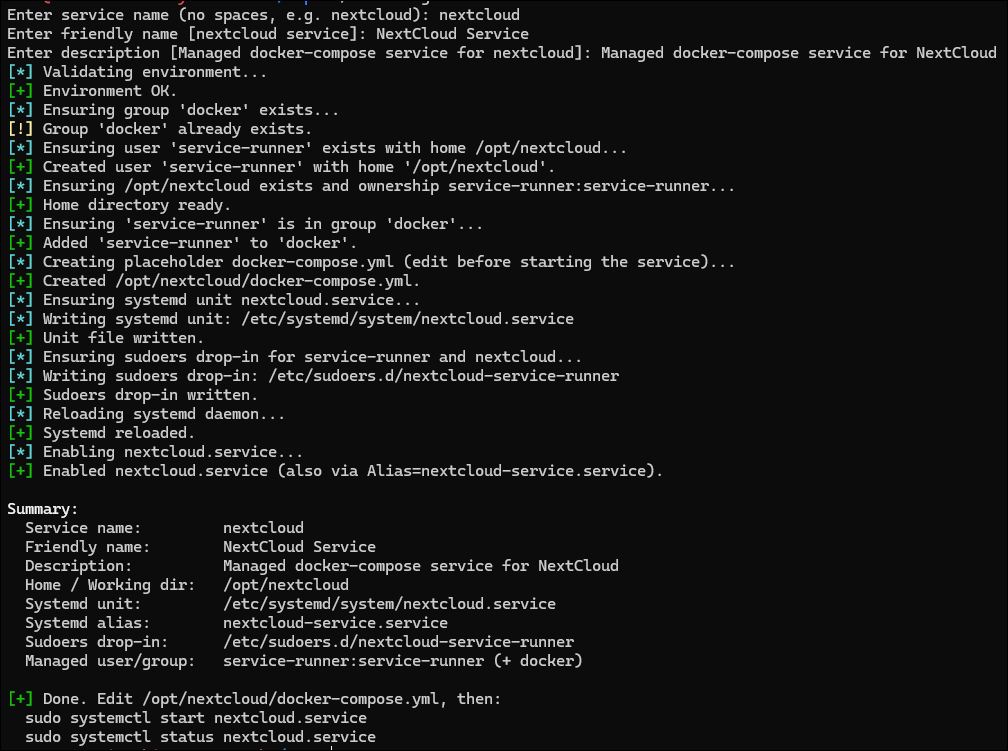

Every service I deploy gets its own directory: /opt/{service-name}. Inside that folder live the docker-compose.yml, .env, and any bind-mounted data directories. My helper script service-generator.sh automates the rest:

- Service user: It ensures

service-runnerexists, has/usr/sbin/nologinas the shell, home directory/opt/{service}, and membership in thedockergroup. - Directory ownership: The script creates

/opt/{service}and hands ownership toservice-runner:service-runnerso containers never write as root. - Compose scaffold: A placeholder

docker-compose.ymlappears if I haven’t written one yet, reminding me where everything lives. - Systemd unit:

/etc/systemd/system/{service}.servicerunsdocker compose up -don start anddocker compose downon stop. That gives mesystemctl status grafanaconsistency for every app. - Sudoers drop-in:

service-runnergets permission to start/stop its own unit plus reboot or shut down cleanly without a password prompt.

Make sure you have Docker installed first. See this copy/pastable block from this other post:

Here is that helper script:

Because I only need it once, I typically just put it in the /tmp/ folder:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

# Change to the temp folder:

cd /tmp

# Download the script and output it to `service-generator.sh`:

wget https://gist.githubusercontent.com/robertsinfosec/cadd98813db6860c4e91c65715b72349/raw/1c9052af2ef63d89e53744ce8d7b6a3058b2237d/service-generator.sh -O service-generator.sh

# Mark the script as executable:

chmod +x ./service-generator.sh

# See usage:

./service-generator.sh --help

You can just run it without arguments (e.g. ./service-generator.sh) and it will prompt you for each part:

Or if you run with --help, you can see what to pass in:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

Usage:

./service-generator.sh [--service-name NAME] [--friendly-name "Readable Name"] [--description "Text"] [--force] [--non-interactive]

Examples:

./service-generator.sh --service-name nextcloud \

--friendly-name "NextCloud Cloud Storage Service" \

--description "Service for controlling this local instance of NextCloud."

Flags:

--service-name Systemd unit name (no .service suffix); also directory under /opt.

--friendly-name Human-readable name used for systemd Alias and metadata.

--description Systemd Description= line.

--force Re-apply/overwrite artifacts if they already exist.

--non-interactive Fail if required fields are missing instead of prompting.

-h, --help Show this help.

What’s a systemd service? It’s a unit file describing how Linux should start, stop, and monitor a process. Think of it as “managed init scripts.” When I run

sudo systemctl start paperless.service, systemd reads the unit and executes the Docker Compose commands for me.

Keeping .env Files Private

In most cases you will have some need for storing sensitive information like database passwords, API keys, etc. Rather than storing them directly in the docker-compose.yml, you can create an .env file in the same folder, and store those environment variables there. As an example:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

NC_DOMAIN=cloud.lab.example.com

# Postgres

POSTGRES_DB=nextcloud

POSTGRES_USER=nextcloud

POSTGRES_PASSWORD=Z8P9OuOFFeDsBLpGCa6EPRNK64GKuM5w

# Cloudflare: Create a scoped token in Cloudflare with Zone.DNS:Edit for your zone.

CF_DNS_API_TOKEN=abcdefghijk01234567

CF_API_EMAIL=[email protected]

LETSENCRYPT_EMAIL=[email protected]

I store .env in the same /opt/{service} directory, owned by service-runner with chmod 600. For example:

1

2

3

4

5

# Change the owner of the .env file to service-runner:

sudo chown service-runner:service-runner /opt/nextcloud/.env

# Lock down permissions so only service-runner can read/write:

sudo chmod 600 /opt/nextcloud/.env

Environment variables often contain API keys (like Cloudflare tokens), so they never belong in Git.

Don't include

.envin Git! Add it to your.gitignorefile so you don’t accidentally commit secrets.

Compose automatically reads that file if it's in the same directory as the docker-compose.yml or if you explicitly pass it with env_file: .env.

Warning: Don’t

catyour.envinto shell history or upload it to a pastebin. Treat it like a password manager export.

Sample systemd unit (trimmed)

As discussed, the systemd unit is the definition for a Linux service, or daemon. Here’s a trimmed example of what gets created for each service:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

[Service]

Type=oneshot

RemainAfterExit=yes

WorkingDirectory=/opt/nextcloud

User=service-runner

Group=docker

ExecStart=/usr/bin/docker compose up -d

ExecStop=/usr/bin/docker compose down

This looks minimal, but it’s enough for most services.

Networking and Certificates with Traefik + Cloudflare

Traefik is the single entry point for the Docker Compose service. Every Compose project adds a traefik network and sets labels describing routers, services, and middleware. Traefik terminates TLS, routes based on hostnames, and renews certificates via Let’s Encrypt. Basically, Traefik is the front door to handle all incoming requests.

What’s Let’s Encrypt? It’s a free certificate authority that issues HTTPS certificates automatically. Traefik speaks their ACME protocol to request and renew certs on your behalf. If you don't want to do this, I also have a post on LetsEncrypt in your Homelab.

Because most of my services are only available on my private network, I rely on the DNS-01 challenge: Traefik proves domain control by creating a temporary TXT record via the Cloudflare API. LetsEncrypt requires that you somehow validate that you own the domain before issuing a certificate. You typically either expose a file on your website that LetsEncrypt can check (HTTP-01 challenge), or you can create a DNS record (DNS-01 challenge). Since my homelab services are not publicly accessible, I use the DNS-01 challenge.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

services:

traefik:

image: traefik:v3.1

command:

- "--certificatesresolvers.cf-dns.acme.dnschallenge=true"

- "--certificatesresolvers.cf-dns.acme.dnschallenge.provider=cloudflare"

- "--certificatesresolvers.cf-dns.acme.email=${LETSENCRYPT_EMAIL}"

env_file:

- .env

networks:

- traefik

app:

image: some/service

labels:

- "traefik.http.routers.app.rule=Host(`books.mylab.local`)"

- "traefik.http.routers.app.entrypoints=websecure"

- "traefik.http.routers.app.tls.certresolver=cf-dns"

networks:

- traefik

- default

Heads-up: Cloudflare API tokens should be scoped narrowly (Zone:DNS edit and Read) and stored in the

.envfile with file permissions locked down.

Data Layout & Backups

All service state lives under /opt/{service}. That means the Compose file, .env, media folders, database files, everything. When it’s time to capture a backup I can literally run something like:

1

2

3

sudo systemctl stop paperless.service && \

sudo /usr/local/bin/run-backup.sh /opt/paperless && \

sudo systemctl start paperless.service

Bind mounts in Compose make this simple:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

services:

paperless-ngx:

volumes:

- /opt/paperless/data:/usr/src/paperless/data

- /opt/paperless/media:/usr/src/paperless/media

- /opt/paperless/export:/usr/src/paperless/export

env_file:

- /opt/paperless/.env

Meaning, when I shut down the service and backup /opt/paperless, I get everything: the database, media files, exports, and configuration. Restoring is just as easy: copy the backup back to /opt/paperless, then start the service again. If I used Docker named volumes instead, I’d have to hunt down where Docker stored those files on the host (typically like: /var/lib/docker/volumes/paperless-data/_data).

Why avoid Docker named volumes? They scatter data in

/var/lib/docker/volumes/, which makes selective restores harder. Keeping everything in/opt/{service}means I can rsync or snapshot one folder and call it done.

Pros, Cons, and When to Deviate

My content is "opinionated" as in, this is what works for me. With that said, there are countless ways to self-host. Like everything, here are the trade-offs of this particular pattern.

Pros

- One mental model for every service: log paths, systemctl commands, and backups all behave the same.

- Easy audits:

/optshows me every deployed service at a glance. - Minimal tooling: Ubuntu LTS, Docker, Compose, systemd, Traefik. No custom orchestrator.

- Simple recovery: Rebuild the host, rerun

service-generator.sh, copy backups back, and you’re done.

Cons

- Single host means single point of failure: Maintenance windows and outages are unavoidable.

- Compose updates are manual: I still need to

docker compose pull && systemctl restart fooper service. - Traefik labels can get verbose: If you hate YAML, this won’t cure that.

- Doesn’t scale past one or two nodes: For HA you’ll eventually graduate to Nomad, K3s, or similar.

Tips, Warnings, and Gotchas

Test with a throwaway service (e.g.,

whoami) before trusting important data. It’s easier to debug Traefik labels on something disposable.

Remember that

docker compose logs -fstill works under systemd. Use it to monitor startups before enabling the unit at boot.

If you edit the systemd unit, always run

sudo systemctl daemon-reloadbefore restarting; otherwise changes quietly get ignored.

Conclusion

This pattern isn’t revolutionary, I did not invent fire, it’s just a System that I've evolved that has worked very well for a few dozen services. By standardizing on Docker Compose, a locked-down service-runner account, Traefik, and /opt/{service} folders, I know exactly where to look when something breaks and exactly how to rebuild it after a disaster. The helper script saves time, but the real benefit is consistency.